Medical Laboratories Need to Prepare as Public Health Officials Deal with Latest Coronavirus Outbreak

The CDC has developed a test kit, but deployment to public health laboratories has been delayed by a manufacturing defect

Medical laboratories are on the diagnostic front lines of efforts in the US to contain the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus responsible for the disease COVID-19, which was first reported in Wuhan City, China. SARS-CoV-2 differs from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), which caused an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003.

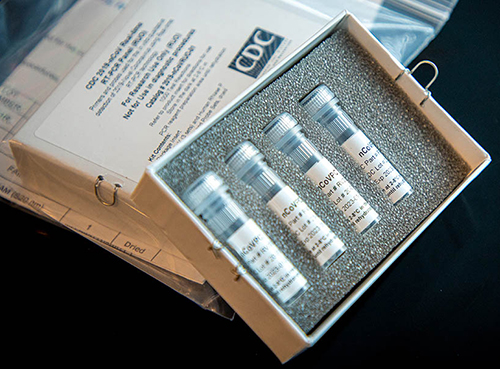

Currently, all testing for SARS-CoV-2 in the US is performed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), using a CDC-developed rapid test known as the 2019-nCoV Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel. But soon, testing will be performed by city and state public health (reference) laboratories as well.

At present, medical laboratories are collecting blood specimens for testing by authorized public health labs. However, clinical laboratories should prepare for the likelihood they will be called on to perform the testing using the CDC test or other tests under development.

“We need to be vigilant and understand everything related to the testing and the virus,” said Bodhraj Acharya, PhD, Manager of Chemistry and Referral Testing at the Laboratory Alliance of Central New York, in an exclusive interview with Dark Daily. “If the situation comes that you have to do the testing, you have to be ready for it.”

The CDC has set up a website with information about SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) including a section specifically for laboratory professionals. The “Information for Health Departments on Reporting a Person Under Investigation (PUI) or Laboratory-Confirmed Case for COVID-19” section includes guidelines for collecting, handling, and shipping specimens. It also has laboratory biosafety guidelines.

The current criteria for determining PUIs include clinical features, such as fever or signs of lower respiratory illness, combined with epidemiological risks, such as recent travel to China or close contact with a laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 patient. The CDC notes that “criteria are subject to change as additional information becomes available” and advises healthcare providers to consult with state or local health departments if they believe a patient meets the criteria.

Test Kit Problems Delay Diagnoses

On Feb. 4, the FDA issued a Novel Coronavirus Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) allowing state and city public health laboratories, as well as Department of Defense (DoD) labs, to perform presumptive qualitative testing using the Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) diagnostic panel developed by the CDC. Two days later, the CDC began distributing the test kits, a CDC statement announced. Each kit could test 700 to 800 patients, the CDC said, and could provide results from respiratory specimens in four hours.

However, on Feb. 12, the agency revealed in a telebriefing that manufacturing problems with one of the reagents had caused state laboratories to get “inconclusive laboratory results” when performing the test.

“When the state receives these test kits, their procedure is to do quality control themselves in their own laboratories,” said Nancy Messonnier, MD, Director of the CDC National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), during the telebriefing. “Again, that is part of the normal procedures, but in doing it, some of the states identified some inconclusive laboratory results. We are working closely with them to correct the issues and as we’ve said all along, speed is important, but equally or more important in this situation is making sure that the laboratory results are correct.”

During a follow-up telebriefing on Feb. 14, Messonnier said that the CDC “is reformulating those reagents, and we are moving quickly to get those back out to our labs at the state and local public health labs.”

Serologic Test Under Development

The current test has to be performed after a patient shows symptoms. The “outer bound” of the virus’ incubation period is 14 days, meaning “we expect someone who is infected to have symptoms some time during those 14 days,” Messonnier said. Testing too early could “produce a negative result,” she continued, because “the virus hasn’t established itself sufficiently in the system to be detected.”

Messonnier added that the agency plans to develop a serologic test that will identify people who were exposed to the virus and developed an immune response without getting sick. This will help determine how widespread it is and whether people are “seroconverting,” she said. To formulate this test, “we need to wait to draw specimens from US patients over a period of time. Once they have all of the appropriate specimens collected, I understand that it’s a matter of several weeks” before the serologic test will be ready, she concluded.

“Based on what we know now, we believe this virus spreads mainly from person to person among close contacts, which is defined [as] about six feet,” Messonnier said at the follow-up telebriefing. Transmission is primarily “through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes. People are thought to be the most contagious when they’re most symptomatic. That’s when they’re the sickest.” However, “some spread may happen before people show symptoms,” she said.

The virus can also spread when people touch contaminated surfaces and then touch their eyes, nose, or mouth. But it “does not last long on surfaces,” she said.

Where the Infection Began

SARS-CoV-2 was first identified during an outbreak in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. Soon thereafter, hospitals in the region “were overwhelmed” with cases of pneumonia, Dr. Acharya explained, but authorities could not trace the disease to a known pathogen. “Every time a new pathogen originates, or a current pathogen mutates into a new form, there are no molecular tests available to diagnose it,” he said.

So, genetic laboratories used next-generation sequencing, specifically unbiased nontargeted metagenomic RNA sequencing (UMERS), followed by phylogenetic analysis of nucleic acids derived from the hosts. “This approach does not require a prior knowledge of the expected pathogen,” Dr. Acharya explained. Instead, by understanding the virus’ genetic makeup, pathology laboratories could see how closely it was related to other known pathogens. They were able to identify it as a Betacoronavirus (Beta-CoVs), the family that also includes the viruses that cause SARS and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS).

This is a fast-moving story and medical laboratory leaders are advised to monitor the CDC website for continuing updates, as well as a website set up by WHO to provide technical guidance for labs.

—Stephen Beale

Related Information:

CDC: Information for Laboratories

About Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

Real-Time RT-PCR Panel for Detection 2019-Novel Coronavirus

Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak

Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Technical Guidance: Laboratory Testing for 2019-nCoV in Humans

Novel Coronavirus Lab Protocols and Responses: Next Steps

WHO: China Leaders Discuss Next Steps in Battle Against Coronavirus Outbreak

Transcript for CDC Telebriefing: CDC Update on Novel Coronavirus February 12

Transcript for CDC Media Telebriefing: Update on COVID-19 February 14

Shipping of CDC 2019 Novel Coronavirus Diagnostic Test Kits Begins