University of Illinois Study Concludes Regular Physical Exercise Improves Human Microbiome; Might Be Useful Component of New Treatment Regimens for Cancer and Other Chronic Diseases

Exercise contributes to improving the human microbiome in ways that fight disease and clinical labs might eventually provide tests that help track beneficial changes in a patient’s microbiome

With growing regularity, new discoveries about the human Microbiome have been reported in scientific journals and the media. Some of these discoveries have led to innovations in clinical laboratory tests over the past few years. Dark Daily reported on these breakthroughs, which include: improved cancer drugs, life extension, personalized medical treatments (AKA, precision medicine), genetic databases, and women’s health.

Now, a study from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UI) has linked exercise to beneficial changes in the makeup of human microbiota. The researchers identified significant differences in the gut bacteria of obese and lean individuals who underwent the same endurance training. The lean individuals developed healthy gut bacteria at a much higher rate than the obese participants. And they retained it, so long as the exercise continued.

Thus, researchers believe weight loss and regular exercise could become critical components of new treatment regimens for many chronic diseases, including cancer.

Regular Exercise Increases Good Gut Bacteria in Humans and Mice

The UI researchers published the results of their study in Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, a journal of the American College of Sports Medicine. To perform their study, they analyzed the impact six weeks of endurance training had on the gut bacteria of 32 adults:

- Eighteen of the subjects were lean and the remaining 14 were obese;

- Eleven of the obese and nine of the lean participants were female; and,

- All 32 were sedentary before the study began.

The subjects participated in six weeks of supervised exercise three days/week. They started at 30-minutes/day and progressed to 60-minutes/day. Fecal samples were collected from the participants before and after the six weeks of training. The subjects were instructed to not change any of their dietary habits during the study.

Upon completion of the initial six-week exercise program, participants returned to a sedentary lifestyle for another six weeks and then researchers took more fecal samples.

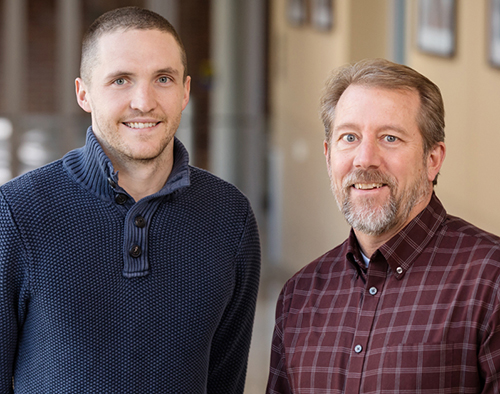

In a University of Illinois study, Jacob Allen, PhD-Candidate (left), and Jeffrey Woods, PhD (right), et al, concluded that regular exercise increased production of beneficial gut bacterial (microbiome) more in lean individuals than in obese participants. This finding could alter how anatomic pathologists and medical laboratories view exercise and weight loss for patients undergoing treatment regimens for chronic diseases. (Photo copyright: University of Illinois/L. Brian Stauffer.)

As a result of the study, the researchers found the gut bacteria of the subjects did change, however, those changes varied among the participants. Fecal concentrations of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), particularly butyrate, increased in the guts of the lean participants but not in the guts of the obese subjects.

SCFAs have been shown to improve metabolism and reduce inflammation in the body, and they are the main source of energy for the cells lining the colon. However, nearly all of the beneficial changes in the participants’ gut bacteria disappeared after six weeks of non-exercise.

“The bottom line is that there are clear differences in how the microbiome of somebody who is obese versus somebody who is lean responds to exercise,” Jeffrey Woods, PhD, Professor, Department of Kinesiology and Community Health, College of Applied Health Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and co-leader of the study, told UI’s News Bureau. “These are the first studies to show that exercise can have an effect on your gut independent of diet or other factors.”

Reduced Inflammation Promotes Healing

The researchers had previously performed a related study using lab mice and found similar results. For that experiment, mice were separated into two groups where some were permitted to run around and be active while the others were sedentary. The gut material from all of the mice was then transplanted into gnotobiotic (germ-free) mice where their microbiomes were exposed to a substance that was known to cause irritation and inflammation in the colon. The animals with the gut bugs from the active mice experienced less inflammation and were better than the sedentary mice at resisting and healing tissue damage.

“We found that the animals that received the exercised microbiota had an attenuated response to a colitis-inducing chemical,” Jacob Allen, PhD Candidate, co-leader of the study and former doctoral student at UI, now a postdoctoral researcher at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, told the UI News Bureau. “There was a reduction in inflammation and an increase in the regenerative molecules that promote a faster recovery.”

Exercise Added to Growing List of Benefits from Health Gut Bacteria

Similar research in the past has found that healthy gut bacteria may have many positive effects on the body, including:

- Improved immune health;

- Improved mood and mental health;

- Boosting energy levels;

- Improved cholesterol levels;

- Regulated hormone levels;

- Reduction of yeast infections;

- Healthy weight support;

- Improved oral health; and,

- Increased life expectancy.

Other ways to improve gut bacteria include: dietary changes, taking probiotics, lowering stress levels, and getting enough sleep. Now regular exercise can be added to this growing list.

Once further research confirms the findings of this study and useful therapies are developed from this knowledge, clinical laboratories should be able to provide microbiome testing that would help physicians and patients track the benefits of exercise on enhancing gut bacteria.

—JP Schlingman

Related Information:

Exercise Alters Our Microbiome. Is That One Reason It’s So Good for Us?

Exercise Alters Gut Microbiota Composition and Function in Lean and Obese Humans

Exercise Changes Gut Microbial Composition Independent of Diet, Team Reports

Exercise Can Beneficially Alter the Composition of Your Gut Microbiome