Advancements That Could Bring Proteomics and Mass Spectrometry to Clinical Laboratories

Experts list the top challenges facing widespread adoption of proteomics in the medical laboratory industry

Year-by-year, clinical laboratories find new ways to use mass spectrometry to analyze clinical specimens, producing results that may be more precise than test results produced by other methodologies. This is particularly true in the field of proteomics.

However, though mass spectrometry is highly accurate and fast, taking only minutes to convert a specimen into a result, it is not fully automated and requires skilled technologists to operate the instruments.

Thus, although the science of proteomics is advancing quickly, the average pathology laboratory isn’t likely to be using mass spectrometry tools any time soon. Nevertheless, medical laboratory scientists are keenly interested in adapting mass spectrometry to medical lab test technology for a growing number of assays.

Molly Campbell, Science Writer and Editor in Genomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics, and Biopharma at Technology Networks, asked proteomics experts “what, in their opinion, are the greatest challenges currently existing in proteomics, and how can we look to overcome them?” Here’s a synopsis of their answers:

Lack of High Throughput Impacts Commercialization

Proteomics isn’t as efficient as it needs to be to be adopted at the commercial level. It’s not as efficient as its cousin genomics. For it to become sufficiently efficient, manufacturers must be involved.

John Yates III, PhD, Professor, Department of Molecular Medicine at Scripps Research California campus, told Technology Networks, “One of the complaints from funding agencies is that you can sequence literally thousands of genomes very quickly, but you can’t do the same in proteomics. There’s a push to try to increase the throughput of proteomics so that we are more compatible with genomics.”

For that to happen, Yates says manufacturers need to continue advancing the technology. Much of the research is happening at universities and in the academic realm. But with commercialization comes standardization and quality control.

“It’s always exciting when you go to ASMS [the conference for the American Society for Mass Spectrometry] to see what instruments or technologies are going to be introduced by manufacturers,” Yates said.

There are signs that commercialization isn’t far off. SomaLogic, a privately-owned American protein biomarker discovery and clinical diagnostics company located in Boulder, Colo., has reached the commercialization stage for a proteomics assay platform called SomaScan. “We’ll be able to supplant, in some cases, expensive diagnostic modalities simply from a blood test,” Roy Smythe, MD, CEO of SomaLogic, told Techonomy.

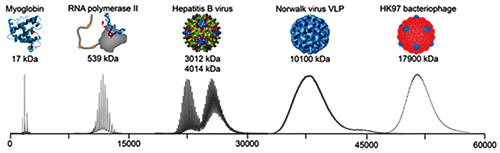

The graphic above illustrates the progression mass spectrometry took during its development, starting with small proteins (left) to supramolecular complexes of intact virus particles (center) and bacteriophages (right). Because of these developments, today’s medical laboratories have more assays that utilize mass spectrometry. (Photo copyright: Technology Networks/Heck laboratory, Utrecht University, the Netherlands.)

Achieving the Necessary Technical Skillset

One of the main reasons mass spectrometry is not more widely used is that it requires technical skill that not many professionals possess. “For a long time, MS-based proteomic analyses were technically demanding at various levels, including sample processing, separation science, MS and the analysis of the spectra with respect to sequence, abundance and modification-states of peptides and proteins and false discovery rate (FDR) considerations,” Ruedi Aebersold, PhD, Professor of Systems Biology at the Institute of Molecular Systems Biology (IMSB) at ETH Zurich, told Technology Networks.

Aebersold goes on to say that he thinks this specific challenge is nearing resolution. He says that, by removing the problem created by the need for technical skill, those who study proteomics will be able to “more strongly focus on creating interesting new biological or clinical research questions and experimental design.”

Yates agrees. In a paper titled, “Recent Technical Advances in Proteomics,” published in F1000 Research, a peer-reviewed open research publishing platform for scientists, scholars, and clinicians, he wrote, “Mass spectrometry is one of the key technologies of proteomics, and over the last decade important technical advances in mass spectrometry have driven an increased capability of proteomic discovery. In addition, new methods to capture important biological information have been developed to take advantage of improving proteomic tools.”

No High-Profile Projects to Stimulate Interest

Genomics had the Human Genome Project (HGP), which sparked public interest and attracted significant funding. One of the big challenges facing proteomics is that there are no similarly big, imagination-stimulating projects. The work is important and will result in advances that will be well-received, however, the field itself is complex and difficult to explain.

Emanuel Petricoin, PhD, is a professor and co-director of the Center for Applied Proteomics and Molecular Medicine at George Mason University. He told Technology Networks, “the field itself hasn’t yet identified or grabbed onto a specific ‘moon-shot’ project. For example, there will be no equivalent to the human genome project, the proteomics field just doesn’t have that.”

He added, “The equipment needs to be in the background and what you are doing with it needs to be in the foreground, as is what happened in the genomics space. If it’s just about the machinery, then proteomics will always be a ‘poor step-child’ to genomics.”

Democratizing Proteomics

Alexander Makarov, PhD, is Director of Research in Life Sciences Mass Spectrometry (MS) at Thermo Fisher Scientific. He told Technology Networks that as mass spectrometry grew into the industry we have today, “each new development required larger and larger research and development teams to match the increasing complexity of instruments and the skyrocketing importance of software at all levels, from firmware to application. All this extends the cycle time of each innovation and also forces [researchers] to concentrate on solutions that address the most pressing needs of the scientific community.”

Makarov describes this change as “the increasing democratization of MS,” and says that it “brings with it new requirements for instruments, such as far greater robustness and ease-of-use, which need to be balanced against some aspects of performance.”

One example of the increasing democratization of MS may be several public proteomic datasets available to scientists. In European Pharmaceutical Review, Juan Antonio Viscaíno, PhD, Proteomics Team Leader at the European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) wrote, “These datasets are increasingly reused for multiple applications, which contribute to improving our understanding of cell biology through proteomics data.”

Sparse Data and Difficulty Measuring It

Evangelia Petsalaki, PhD, Group Leader EMBL-EBI, told Technology Networks there are two related challenges in handling proteomic data. First, the data is “very sparse” and second “[researchers] have trouble measuring low abundance proteins.”

Petsalaki notes, “every time we take a measurement, we sample different parts of the proteome or phosphoproteome and we are usually missing low abundance players that are often the most important ones, such as transcription factors.” She added that in her group they take steps to mitigate those problems.

“However, with the advances in MS technologies developed by many companies and groups around the world … and other emerging technologies that promise to allow ‘sequencing’ proteomes, analogous to genomes … I expect that these will not be issues for very long.”

So, what does all this mean for clinical laboratories? At the current pace of development, its likely assays based on proteomics could become more common in the near future. And, if throughput and commercialization ever match that of genomics, mass spectrometry and other proteomics tools could become a standard technology for pathology laboratories.

—Dava Stewart

Related Information:

5 Key Challenges in Proteomics, As Told by the Experts

The Evolution of Proteomics—Professor John Yates

The Evolution of Proteomics—Professor Ruedi Aebersold

The Evolution of Proteomics—Professor Emanuel Petricoin

The Evolution of Proteomics—Professor Alexander Makarov

The Evolution of Proteomics—Dr. Evangelia Petsalaki

For a Clear Read on Our Health, Look to Proteomics

Recent Technical Advances in Proteomics

Emerging Applications in Clinical Mass Spectrometry

Open Data Policies in Proteomics Are Starting to Revolutionize the Field

Native Mass Spectrometry: A Glimpse Into the Machinations of Biology