With $175 Million in Funding, Human Microbiome Project is Making Rapid Progress

Research into the human microbiome is expected to trigger development of new diagnostic tests that will be offered by clinical pathology laboratories. That’s because the organisms that live on us and in us are as unique to individuals as their DNA, and scientists believe these microbes may be just as important to health. Which microbes and how much they matter to the host’s health are the questions a consortium of researchers involved in the Human Microbiome Project (HMP) hope to answer.

This five-year, $157-million project, funded by the National Institutes of Health, will sequence and classify 900 microbes believed to play a role in human health. Analysis of the sequences of the first 178 microbes, which was published in the May 21 issue of Science, held some surprises, particularly in regard to the extent and complexity of microbial diversity. About 90% of their DNA was previously unknown. The study also identified novel genes and proteins that contribute to human health and disease.

In an ABC News report, Karen Nelson, Ph.D., who heads HMP research at the J. Craig Venter Institute, noted. “We are dependent on them [microbes] for digestion of plant material and some vitamins.” But healthy colonies of microbes, which outnumber human cells 10 to 1, may affect a variety of aspects of human health, ranging from pH balance on skin to protection against tooth decay, intestinal infections, and sexually transmitted disease.

New genomic techniques can identify minute amounts of microbial DNA in an individual and determine its identity by comparing the genetic signature to known sequences in the growing HMP catalog of microbial genomes, noted scientists at the Genome Center at Washington University in St. Louis, which decoded about half of these microbes in the initial study.

Liping Zhao, Ph.D., noted in an article in Journal of Biotechnology, that humans are “superorganisms with two genomes, the genetically-inherited human genome and the environmentally-acquired human microbiome. But unlike the human genome, “the gene composition of the human microbiome is rather flexible and can be modulated by foods and drugs.”

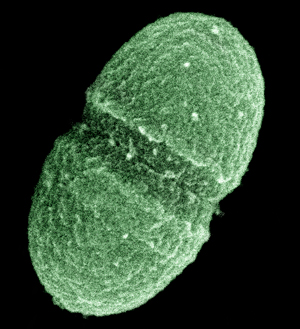

The Human Microbiome Project is studying this bacterium,

Enterococcus faecalis, which lives in the human gut.

(Photo courtesy of U.S. Department of Agriculture.)

Cataloging microbial communities and how they change in response to certain drugs or environmental factors will enable scientists to apply them to medical uses, including clinical laboratory testing. But some scientists are already taking this research to the next level, focusing on how microbes affect specific health conditions and ways to use this information to guide medical interventions.

For example, researchers Rob Knight, Ph.D., a microbiologist and assistant professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, and Jeff Gordon, M.D., Dr. Robert J. Glaser Distinguished University Professor of Pathology and Immunology at Washington University, are collaborating on research into the role microbes play in metabolism and obesity in children.

Knight had previously shown in animal studies that microbes can effect weight gain. Transplanting microbes from fat mice into normal mice caused them to eat more and gain weight. Knight was able to test this finding on a human subject, himself, after returning from Mexico with a bad case of “Montezuma’s revenge” and taking a regime of antibiotics.

By testing the colonies of organisms in his own gut before and after taking antibiotics, he was able to analyze how the antibiotics changed the microbial populations. Previously Knight had engaged in a diet and exercise program, but had been unsuccessful in losing weight. After taking the antibiotic regime he restarted the program and lost 60 pounds. “The conjecture was that the antibiotics might clear out the microbes that were already there and make it easier to reshape the community,” he surmised.

Knight and Gordon are also studying how gut microbes affect children’s ability to gain weight. They note that peanut butter, powdered milk, and vitamins have helped many children suffering from malnutrition in poor nations, but some children do not respond to this nutritional regime (via jones www.dresshead.com). Noting that identical twins living in the same household may respond differently to nutrition, they suggest that these children have picked up a pathogen that causes malnutrition or lost some type of microbe.

Ultimately, Knight and Gordon hope to translate their work into diagnostic tests that could predict how an individual will respond to antibiotics or other drugs and environmental factors and develop diet programs tailored to the individual’s unique microbiome. Knight says, however, “There are lots of things we can do potentially right now using microbes as markers.”

Zhao is heading a study at BGI, a Chinese institute with massive sequencing power, that takes this research to the next level. (See Dark Daily “Why China Is Now the World Leader in Genome Sequencing Capacity,”) In an initial study, the microbial communities of subjects were analyzed prior to starting a special diet. Some gained weight and others lost, but Zhao was able to predict who would lose or gain weight by looking at their microbial makeup before starting the diet.

For pathologists and clinical laboratory managers, the rapid expansion of knowledge about the human microbiome demonstrates how new fields of science can change laboratory medicine by creating different approaches to detect and diagnose a range of diseases and health conditions. In the case of the human microbiome, it will be genetic and molecular pathology testing technologies which will be used to identify and type the unique microbes found in individual humans.

Related Information:

Scientists decode DNA of microbes from humans

Human Gene Catalog Shows It’s Mostly a Mystery

Consortium Finds Greater Microbial Diversity in Human Microbiome than Previously Known

Effort to Map Human Microbiome Will Generate Useful New Clinical Lab Tests for Pathologists

Why China Is Now the World Leader in Genome Sequencing Capacity